Please note – The primary objective of residential and subdivision street design is to provide safe, efficient vehicular access to residential homes, schools, playgrounds, and other neighborhood activities. This chapter addresses some basic considerations that should be evaluated in the design and construction of such streets and roads. Many localities have established certain standards and requirements for residential streets, as has the Virginia Department of Transportation. All applicable sections of these state and local requirements should be followed. The information contained herein is provided as an additional reference source for basic design and construction considerations.

Please note – The primary objective of residential and subdivision street design is to provide safe, efficient vehicular access to residential homes, schools, playgrounds, and other neighborhood activities. This chapter addresses some basic considerations that should be evaluated in the design and construction of such streets and roads. Many localities have established certain standards and requirements for residential streets, as has the Virginia Department of Transportation. All applicable sections of these state and local requirements should be followed. The information contained herein is provided as an additional reference source for basic design and construction considerations.

Planning and Geographic Considerations

Residential street design standards can control the movement of traffic and help establish desirable traffic patterns. The speed at which motorists drive the routes they select can be influenced by street configuration. Residential streets and roads by design are low speed, low traffic, and short trip facilities. Truck traffic should be limited to only vehicles that provide residential services such as trash pickup, heating oil delivery, moving vans, etc. All designs must be sufficiently flexible to accommodate the particular needs and geography which exist in various parts of Virginia.

Residential street design standards can control the movement of traffic and help establish desirable traffic patterns. The speed at which motorists drive the routes they select can be influenced by street configuration. Residential streets and roads by design are low speed, low traffic, and short trip facilities. Truck traffic should be limited to only vehicles that provide residential services such as trash pickup, heating oil delivery, moving vans, etc. All designs must be sufficiently flexible to accommodate the particular needs and geography which exist in various parts of Virginia.

As is the case in planning all types of roadway facilities, it is absolutely essential that maximum safety features be built into street systems. Right angle intersections provide better visibility in all directions for the driver, as well as shorter crossing distances. The installation of underground wiring for electric and telephone utilities is desirable for both safety and aesthetics.

Special Considerations

The two most important considerations in designing a pavement are traffic and drainage. If either is not adequately accounted for in the pavement design, the pavement structure will either be over-designed (and money wasted) or under designed (and result in premature and continual maintenance).

Many subdivision and residential streets are initially under designed and result in pavement failure taking place prior to the completion of the housing in the area. Damage is often caused by the overloading of the pavement by construction vehicles. In establishing the pavement design, consideration should be given to using a layered asphalt pavement with the final surface being placed after home construction has been completed. This type of construction technique permits the patching of any areas of pavement failure prior to final surfacing.

Many subdivision and residential streets are initially under designed and result in pavement failure taking place prior to the completion of the housing in the area. Damage is often caused by the overloading of the pavement by construction vehicles. In establishing the pavement design, consideration should be given to using a layered asphalt pavement with the final surface being placed after home construction has been completed. This type of construction technique permits the patching of any areas of pavement failure prior to final surfacing.

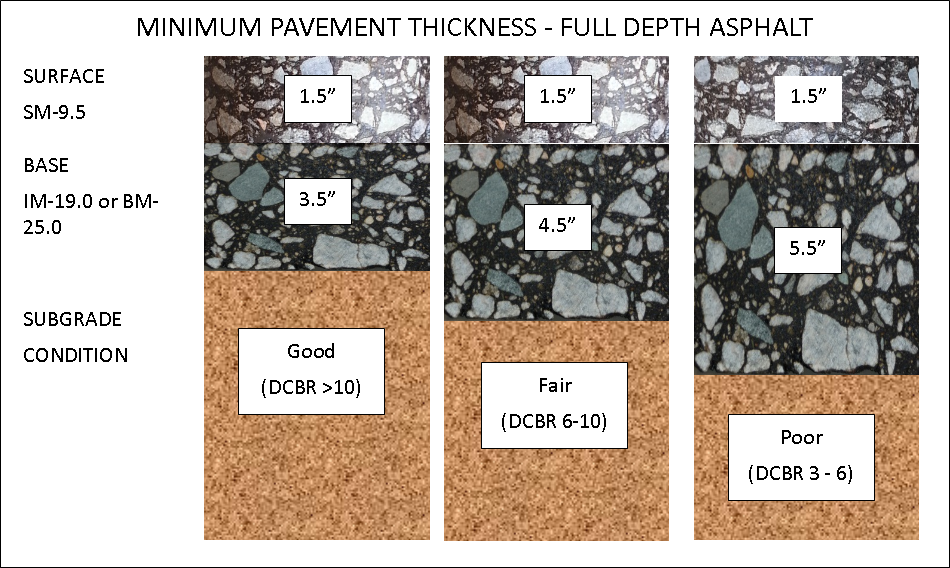

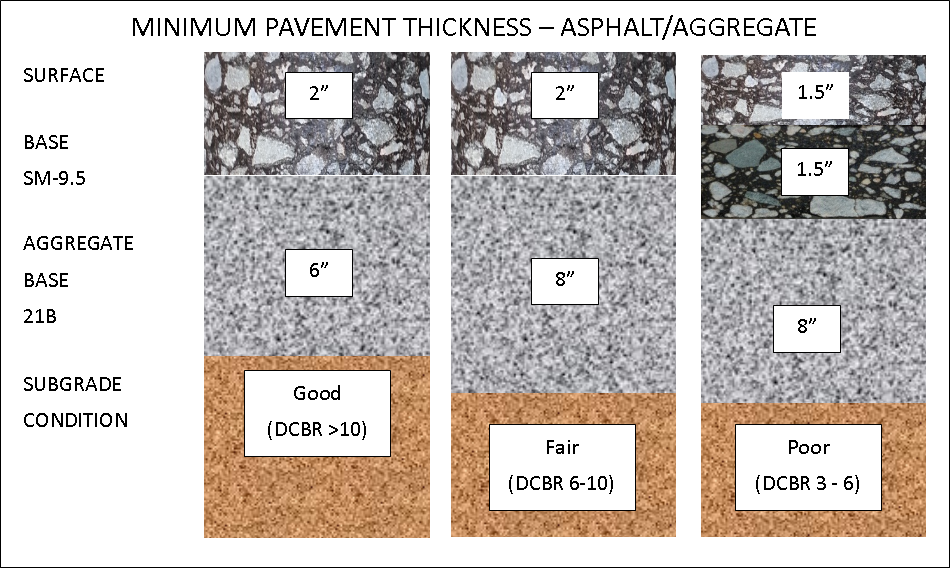

The thickness designs given in this chapter are minimum compacted thickness recommendations. Any reduction of the pavement thickness values shown for base or surface thicknesses may cause severe pavement failure.

Traffic Analysis

All asphalt pavements must be designed using proper loading data to ensure adequate pavement performance. In residential street and road design, this data should be based on vehicular traffic estimates for the pavement’s design life. These estimates should include accurate counts of vehicles by type, weight, and number.

This design manual considers residential streets to be light duty streets with traffic, both present, and future, limited almost entirely to passenger cars plus normal service trucks (moving vans, trash trucks, home heating oil delivery, school buses, etc.). Any deviation from this assumption will require adjustments to the pavement designs shown in the table below.

This design manual considers residential streets to be light duty streets with traffic, both present, and future, limited almost entirely to passenger cars plus normal service trucks (moving vans, trash trucks, home heating oil delivery, school buses, etc.). Any deviation from this assumption will require adjustments to the pavement designs shown in the table below.

The effects of truck traffic on pavement life can be dramatic. Test results have shown that a single, fully loaded, 80,000-pound truck can cause the equivalent in pavement wear of 9,600 automobiles. While these test results may only approximate wear caused by heavy vehicles, they do illustrate why estimating traffic type and number is important to determining the proper asphalt pavement design. Residential streets must be designed to accommodate trash trucks, home heating oil delivery vehicles, moving vans and other occasional heavily loaded trucks.

Drainage

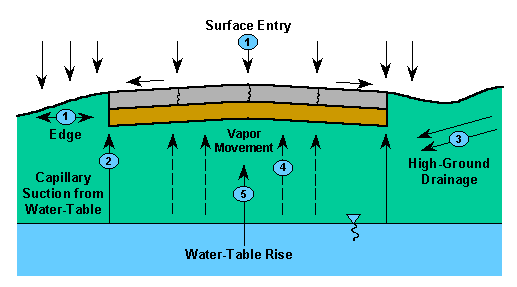

Adequate pavement drainage is of great importance to all pavement designs. If the subgrade under the pavement becomes saturated, it will lose strength and stability and make the overlying pavement structure susceptible to break up under imposed loads. Both surface and subsurface drainage must be considered. All drainage must be carefully designed and should be installed in the construction process as early as is practicable. The pavement should also be constructed in a manner that will not permit water to collect at the pavement edge and provisions should be made to intercept all groundwater from springs, seepage planes, and streams. When used, curb and gutter sections should be set to true line and grade. Marshy areas will require special consideration and should be addressed during the planning stage.

Residential streets often are designed to follow natural drainage ways to permit rapid run-off from building lots. Both surface and subsurface drainage must be given careful attention to prevent accumulation of water. Where drainage is unusually difficult, it may be necessary to increase pavement thickness and install subgrade underdrains. (Underdrains are usually not required when full depth asphalt is used.)

Drainage impacts pavement performance when the subgrade materials and pavement layer materials are saturated and lose strength. Water that falls on the pavement surface must be drained to curb and gutter systems or ditches. Water that penetrates the pavement from the surface; infiltrates from the sides of the road, or rises from under the pavement should not be allowed to compromise the overall strength.

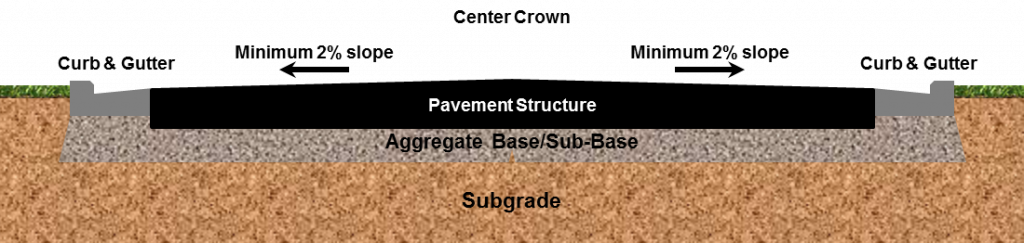

Many subdivision streets are placed at too low an elevation resulting in the pavement carrying run off and acting as a drainage facility. This results in increased maintenance and shorter pavement life. Proper elevation and crown are essential to pavement surface drainage.

To account for surface water drainage, it is important that the road is constructed with a crown or cross slope. Typically, a crown is placed in the center of the road and the pavement is sloped 2% in each direction. Occasionally, the pavement will be super-elevated where one side of the road is higher than the other. In either case, the pavement must be sloped to keep water from ponding on the surface.

For subsurface water, the approach to address varies based on the project. In some situations, underdrains are placed to intercept water that may flow under a pavement. This water is then allowed to flow out into a ditch or is put in a stormwater system. In many cases where the subgrade becomes weaker due to water, the subgrade is stabilized with a binding agent, removed and replaced with a stronger material, covered with a stabilization fabric prior to placing the next pavement layer or the next pavement layers are made thicker.

Soil Support

The ability of the native subgrade soil to support loads transmitted through the pavement is one of the most important factors in determining pavement thickness. The California bearing ratio (CBR) test* provides a simple dependable index of a soil’s load-bearing capacity. It is widely used by many highway departments as well as other governmental agencies on both the state and federal levels.

The strength of the subgrade soil should be established through testing procedures from one of the following:

- Have a reputable materials testing laboratory conduct a subgrade soils test of the project and determine CBR values.

- Contact the local office of the Virginia Department of Transportation for information on results of CBR tests made by the Department on soils In the immediate area.

However, the designer should be aware of the limitations of using averaged CBR values in determining soil support data. Up to one-third of the soil samples used to compute an average CBR will be below that value.

Example

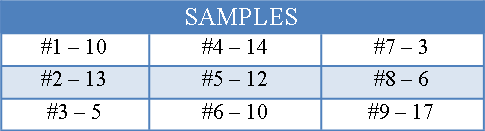

Nine CBR samples are taken on a proposed sub division street in Richmond and their values are as follows:

The average CBR value for these samples is 10. However, samples #3, 7 and 8 were well below 10. If the pavement is designed based on an average CBR value of 10, pavement failures in the areas of test samples 3, 7 and 8 can be expected.

This manual recommends a design CBR value of two-thirds (2/3) the actual average CBR value be used in selecting pavement thickness (the Vaswani design method used by the Virginia Department of Transportation also used a design value of two thirds (2/3) the average CBR value). This will help assure the adequacy of the pavement design.

- ASTM Standard Test Method D 1883

Subgrade Preparation

All underground utilities should be protected or relocated prior to grading because the subgrade must serve both as a working platform to support construction equipment and as the foundation for the structure, it is most important to see that it is properly compacted and graded. A visual examination will usually reveal the adequacy of the elevation. However, laboratory tests to evaluate the load-supporting characteristics of subgrade soil are desirable. If these tests are not available, designs may be chosen based on careful field evaluations and previous projects and experience in the area.

All topsoil should be removed and low-quality soil must be improved by adding asphalt or other suitable admixtures such as lime or granular materials.

The areas to be paved should have all rock, debris, and vegetation matter removed. Grading and compaction of the area should be completed in such a manner as to prevent yielding areas or pumping of the soil. The subgrade should be compacted to a uniform minimum density of 95% of the maximum theoretical density.

Should a weak spot be discovered, the material should be removed and replaced with either six inches (6″) compacted crushed stone or three inches (3″) compacted asphalt concrete. In case of extremely poor subgrade, it may be necessary to remove the upper portion of the subgrade and replace it with a select material. When finished, the graded subgrade should not deviate from the required grade and cross section by more than one-half inch (1/2”) in ten feet (10′).

Base Construction (Asphalt)

Prior to placement of the asphalt concrete base course, the subgrade should be graded to the established requirements, adequately compacted, and all deficiencies corrected. The asphalt concrete base course should be placed directly on the prepared subgrade in one or more lifts, spread, and compacted to the pavement thickness indicated on the plans or established by the owner. (Compaction of asphalt mixtures is one of the most important construction operations contributing to the proper performance of the completed pavement, regardless of the thickness of the course being placed. This is why it is so important to have the properly prepared subgrade against which to compact the overlying pavement.) The asphalt concrete should meet the Virginia Department of Transportation specifications for the mix type specified.

Base Construction (Aggregate)

The subgrade must be graded to the required contours and grade in a manner as will ensure a hard, uniform, well-compacted surface. All subgrade deficiency corrections and drainage provisions should be made prior to constructing the aggregate base.

The crushed aggregate base course should consist of one or more layers placed directly on the prepared subgrade, spread, and compacted to the uniform thickness and density as required on the plans or established by the owner. Absolute minimum crushed aggregate thickness is six inches (6″). All crushed aggregate material should be Virginia Department of Transportation approved and suitable for this type of application.

Tack Coat

Prior to placement of successive pavement layers, the previous course should be cleaned and, if needed, a tack coat of diluted emulsified asphalt applied. If the previous course is freshly placed and thoroughly clean, the tack coat may be eliminated.

Asphalt Surface Course

Material for the surface course should be asphalt concrete placed in one or more lifts to the true line and grade as shown on the plans or set by the owner. The asphalt concrete should conform to Virginia Department of Transportation’s specifications for the specified mix. The asphalt surface should not vary from established grade by more than one-eighth inch ( 1/8″) in ten feet (1 0′) when measured in any direction. Any irregularities in the surface of the pavement course should be corrected directly behind the paver. Rolling and compaction should start as soon as the asphalt concrete can be compacted without displacement and continued until thoroughly compacted and all roller marks disappear.

Curb and Gutter

Designed to provide roadway drainage, curb and gutter also delineate the roadway edge. Gutter widths vary from one (1’) to two (2’) feet, with one-and one half (1-1/2’) feet being most common. Vertical curbs range between five (5”) and eight (8”) inches in height, with a six (6”) inch high curb preferred.

One of the most common errors in residential street design is not specifying the appropriate grades to ensure that water does not collect on the pavement. Many residential and subdivision streets have the elevation of the pavement below that of the curb and gutter. As water is the biggest enemy of any pavement, these “dry curbs” will result in poor pavement performance and shorter pavement life.

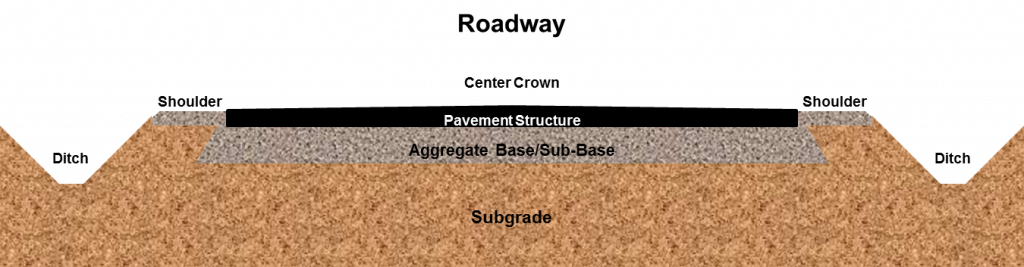

Pavement Structure

The pavement structure and materials used will change as a function of subgrade strength and construction approach. Some projects will use full-depth asphalt (i.e., asphalt placed directly on compacted subgrade) and some will use an aggregate base placed on compacted subgrade. The aggregate base will be covered with one or more layers of asphalt. The table below is the minimum pavement designs. Each layer is the compacted thickness. At no time should less than 4 inches of an aggregate subbase layer be used.

Table 1 – Full-Depth Asphalt Pavement

Table 2 –Asphalt with Aggregate Sub-Base Pavement

Notes:

- Design CBR is defined as 2/3 of the soaked CBR value.

- VDOT Specifications for SM-4.75, SM-9.0, SM-9.5, IM-19.0, and BM-25.0 can be found in Section 211 of the VDOT Road and Bridges Specification Book.

- VDOT Specifications for 21B can be found in Section 208 of the VDOT Road and Bridges Specification Book.

Future Maintenance Considerations

In time, pavement failures may occur due to settlement or weakening of the soil or aggregate base layers. These will result in localized failures or potholes. To repair these failures, the area impacted should be cut out and the pavement material removed to the subgrade. The subgrade material may need to be removed and replaced or simply recompacted. Finally, the removed pavement material should be replaced with new asphalt concrete or a permanent asphalt patching material.

As asphalt ages, shrinkage cracks will develop. Individual transverse and longitudinal cracks should be sealed with an asphalt-based material to reduce the amount of water infiltrating the underlying pavement layers. If the cracking is extensive, then the pavement can be overlaid with a new AC surface or milled and replaced with a new AC surface. Overlaying can be performed on streets without curb and gutter. For streets with curb and gutter, milling may be needed to maintain surface drainage. While edge milling can be performed, typically 4 to 6 feet in width at the edge of the road, full pavement milling is recommended in order to keep proper cross-slope.

References

2016 VDOT Road and Bridges Specifications

VDOT Special Provisions to the 2016 Road and Bridges Specifications